November 2019

Bosworth & King Richard III

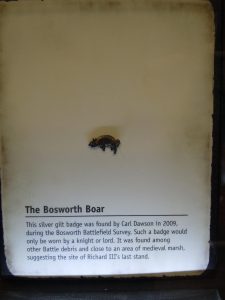

The Battle of Bosworth was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses. The war between the Houses of Lancaster and York had extended across the whole of England but came to a climax in Leicester. The Bosworth visitor centre explains the background to

King Richard and Henry Tudor’s claims to the throne and describes the battle in detail. An excellent exhibition providing a fascinating and interactive experience. After casting our votes for Richard or Henry Tudor we continued on to Leicester.

The KRIII centre in Leicester tells the story of the life and death of King Richard III and how his remains were eventually discovered on the site of the former Grey Friars Church; one of the greatest archaeological detective stories ever told. It was extremely interesting

and enhanced by volunteer John’s wealth of knowledge.

October 2019

HENRY IV

Henry spent much of his reign defending himself against plots, rebellion & assassination attempts. One of the major rebels was the Welsh landowner, Owain Glyndwr, who protested about the oppressive English rule and declared himself Prince of Wales. Henry led many unsuccessful expeditions to Wales but it was not brought under royal control again until his son, later Henry V, managed to do so. Owain Glyndwr allied himself with the powerful Percy family: Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland and his son, Sir Henry

Percy, known as Hotspur. All detailed in Shakespeares Henry IV Parts I/II

September 2019

RICHARD II 1367 – 1399

August 2019

EDWARD III 1312 – 1377

The charismatic Edward III, one of the most dominant personalities of his age, was the son of Edward II and Isabella of France. He was born at Windsor Castle on 13th of November, 1312 and created Earl of Chester at four days old.

It seems Edward had been fond of his father Edward II. By the Autumn of 1330, when he reached eighteen, he strongly resented his political position and Mortimer’s interference in government. Aided by his cousin, Henry, Earl of Lancaster and several of his lords, Edward led a coup d’etat to remove Mortimer from power. They entered Nottingham Castle through the network of caves to arrest Mortimer who had become his mother’s lover and had treasonously deposed and murdered his father King Edward II.

Edward’s maternal grandfather, Phillip IV died in 1314 and was suceeded by his three sons Louis X, Philip V, and Charles IV in succession. On the death of the youngest of Phillip’s sons, Charles IV, the French throne descended to the Capetian Charles IV’s Valois cousin, who then became Phillip VI. As the grandson and nephew of the last Capetian kings, Edward considered himself to be a far nearer relative than a cousin. He quartered the lilies of France with the lions of England in his coat-of-arms and formally claimed the French throne through right of his mother. By doing so Edward began what later came to be known as the Hundred Years War. The conflict was to last for 116 years from 1337 to 1453.

Edward III’s heir, Edward, the Black Prince, the flower of English chivalry, was stricken with illness and died before his father in June, 1376. He was succeeded by his grandson, Richard II, the eldest surviving son of the Black Prince.

The sword of Edward III The great two-handed iron sword of King Edward III still survives to the present day in the royal collection. The sword can be seen in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, the mother chapel of the Order of the Garter, displayed on a pillar in the South Quire Aisle, where it has hung for the past four hundred years. The sword hangs by a portrait of the king depicted with the crowns of England, Scotland and France.

The Black Death. Disaster struck England in Edward III’s reign, in the form of bubonic plague, or the Black Death, which cut a scythe across Europe in the fourteenth century, killing a third of it’s population. It first reached England in 1348 and spread rapidly. In most cases the plague was lethal. Infected persons developed black swellings in the armpit and groin, these were followed by black blotches on the skin, caused by internal bleeding. These symptoms were accompanied by fever and spitting of blood. Contemporary medicine was useless in the face of bubonic plague, it’s remorseless advance struck terror into the hearts of the medieval population of Europe, many in that superstitious age saw it as the vengeance of God. The population of England was decimated.

June 2019

Visit to Lincoln

May 2019

EDWARD II 1284 – 1327

Edward II was the first Prince of Wales to become King of England.

Between 1311 and 1314 Robert Bruce was causing trouble in Scotland, so Edward lead his army to meet him. On 23rd June they meet at Bannockburn where Edward had to cross the ford. This was narrow and he couldn’t get his greater force across so Robert Bruce won the battle.

Edward II was an unpopular king. His constant feuding and general mismanagement of the Nation led to a period of hardship and famine for the general population. In 1326 his wife Isabella, who he was estranged from most of their marriage, crossed over from France with her lover Roger Mortimer to put her son on the throne. Roger and Isabella led a successful invasion and rebellion and Edward II was subsequently deposed. He was compelled to abdicate in favour of his son, who was crowned Edward III of England on 25 January 1327. Edward was legally obligated to rule through the guidance of a Regent until he reached his majority. That Regent of course, was officially his mother Queen Isabella, but the real power behind the Throne, as everyone knew lay in the hands of Roger Mortimer, so for three years, Mortimer was de facto ruler of England. Mortimer allegedly arranged Edward II murder at Berkeley Castle.

In the chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker is one account of Edward’s captivity and death: “He was held in a cell above the rotting corpses of animals, in an attempt to kill him indirectly. But Edward was extremely strong, fit and healthy, and survived the treatment, until on the night of 21 September 1327, he was held down and a red-hot poker pushed into his anus through a drenching-horn. His screams could be heard for miles around”.

The Trip to Jerusalem Inn. A small room, cut out of the rock at the back of the Rock Lounge was known as Mortimer’s Room. This room was connected to the Castle by a small passage through the sandstone rock, known as Mortimer’s Hole. You can access Mortimer’s Hole on a tour from Nottingham Castle. It is said that Roger de Mortimer and Queen Isabella used to meet in secret: he from the Inn and she from the Castle.

April 2019

Edward I (1239 – 1307)

LONGSHANKS

Edward I was over 6 ft tall, hence his nickname Longshanks. He was strong, athletic and a fine horseman. His reign may be seen as a continuation of much that his Great-grandfather Henry II had set in motion. The King concentrated on legal reform, constitutional development and relations with Wales and Scotland.

In April 1284 Edward’s 4th son was born at Caernarfon Castle. The King and Queen christened him Edward and he became the first English prince to be invested with the title of Prince of Wales.

EDWARD I & ELEANOR OF CASTILE

Edward and Eleanor married in 1254. He was 15 and she 13. They were married for 36 years. Edward seems to be one of the few English Kings of the time to be faithful to his wife. It was a loving marriage. They were the first King and Queen to take part in a Coronation together since the Norman Conquest – crowned August 19th 1274 at Westminster Abbey.

They had 14-16 children but only 6 survived childhood.

THE ELEANOR CROSSES

Edward’s beloved wife Eleanor died in Harby, near Lincoln and Edward took her back to London, travelling 12 days. He ordered a cross to be erected where he stopped each night. Three Eleanor crosses still remain at Geddington and Hardingstone in Northamptonshire and at Waltham Cross in Essex. The final monument at Charing Cross in what was then the stables for Westminster Palace. Its location was on the south side of what is now Trafalgar Square.

March 2019

HENRY III (1207 – 1272)

HENRY OF WINCHESTER

Son of King John, Henry succeeded to the throne at 9 years of age. He had 2 coronations.: The first at Gloucester Cathedral when half of his kingdom was in the hands of rebel barons who wanted King Louis of France to be King of England; Later, in Westminster Abbey when the French had been expelled and he had made peace with the barons.

Much of what constitutes the Tower of London today is a result of Henry’s work from 1238 onwards. He added to the royal menagerie with many animals unknown to England including leopards, elephants and a polar bear which fished in the Thames. He built Westminster Abbey as a shrine to Edward the Confessor. In 1272 when Henry died, his body was buried in Westminster Abbey, beside Edward’s shrine and his heart was buried at the Abbey at Fontevrault, France.

In total Henry III reigned for 56 years, making him the fourth longest reigning monarch after Elizabeth II, Victoria and George III.

SIMON DE MONTFORT (2nd) 1208-1265

Born in France in 1208, he came to England in 1229 to pursue his claim to Leicester which he ultimately gained. He was styled Earl of Leicester in 1239. He quickly became one of Henry III’s favourites and married Henry’s widowed sister, Eleanor. The King appointed Simon Governor of Gascony. In the 1250s there was a lot of bickering between Simon and the King because of the way that Simon ruled but after reconciliation he was given Kenilworth Castle.

Henry III ruled badly and Simon kept urging him to act on the provisions of the Magna Carta. Discontent with the way Henry was ruling increased and some of the most important magnates began to think that Henry needed to be restrained as he was capable of political mischief, as his father, John, beforehand. The Council of Fifteen became the supreme board of control over the administration and the Provisions of Oxford were written.

In 1261, Henry revoked his assent to the Provisions of Oxford and de Montfort, in despair, left the country. While de Montfort was away in France Henry took advantage of the dissent among the barons to restore his fortune. Simon de Montfort returned to England in 1263, at the invitation of the barons who were convinced of the Kings hostility to the reforms. He found the whole country in disarray. By the summer of 1263 Simon and his allies had captured most of south-east England. He now styled himself “Steward of England” and was virtually the supreme ruler but he was unable to prevent civil war. He died fighting King Henry’s son Edward at the battle of Evesham in August 1265.

January/February 2019

THE MAGNA CARTA

Heavy taxation, the loss of English territories in France and a dispute with Rome over the Pope’s choice of Archbishop of Canterbury led to the drawing up of the Magna Carta in 1215.

It laid down respective rights and responsibilities of citizens and the Church in relation to the power of the crown. The Barons, led by Stephen Langton, drew up a list of demands and threatened civil war if King John did not agree to them. There were 63 clauses which limited the King’s power in relation to taxation of the Barons, the rights of the Church and city corporations and stated that no free man could be arrested and imprisoned except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the laws of the land.

It was sealed by King John on 15th June 1215, reissued in 1216 with some clauses removed and the final version was agreed by Henry III in 1225. It is considered to be a milestone in English constitutional history.

Twenty five Barons were responsible for monitoring King John’s future conduct. We looked at these Barons, who they were and where they came from and we discussed the clauses which are still in use.

Shortly afterwards the First Baron’s War erupted. The Pope had declared the charter to be null and void as the King had been forced to sign it under duress. The rebel barons concluded that peace with John was impossible and turned to Philip II’s son, the future Louis VIII for help, offering him the English throne. King John became ill and died on the night of 18 October 1216, leaving nine-year-old Henry III as his heir.

We are planning a trip to Lincoln in the Spring to see the Magna Carta.

December 2018

KING JOHN

Shakespeare’s King John gives a bad impression of King John. The stories of Robin Hood show Richard the Lionheart as good and King John as bad. As we saw when we looked at Richard I those stories don’t describe the truth of the situation and many things about John were good. He was born on Christmas Eve in 1167 when his mother Eleanor was 45 years old and she never showed much interest in him. He was the runt of the litter, in the shadow of 3 much older brothers, and failed on his first venture – to re-establish the King’s justice in Ireland. He was known as Lackland, as he lacked territory.

He was loyal to his father until the last minute change of allegiance when he joined with Richard. He became King at the age of 31 on his brother Richard’s death but there was another claimant. Richard had earlier nominated Arthur of Brittany as his successor so his realms were divided. When John became King his mother Eleanor was still alive so Aquitaine remained loyal to her and to John. Normandy and England also opted for John but Anjou, Maine and Touraine chose Arthur. John was immediately a strong King and after twelve months it was agreed that Arthur retain Brittany with John as his overlord. A treaty was agreed with Philip of France and John was recognised as the Angevin ruler.

John’s first wife was barren and in 1200 he married Isabelle of Angouleme who bore him 5 children including the future Henry III. This marriage caused problems in France and Philip of France used this discontent as a pretext to invade Normandy and to recognise Arthur of Brittany as the rightful ruler of Angevin. In the battle to keep land that Eleanor was holding for King John, Arthur was captured and murdered. Shakespeare’s version is possibly not true but King John did kill his nephew.+————–

John was a hard worker who took the responsibilities of Government very seriously and cared about justice. Many English towns owe their charters to him. On the 19th June 1215 the Magna Carta was signed at Runnymede.

November 2018

This month we looked at a variety of things:

The Crusades.

First the crusades, which were an attempt to conquer the Holy Land , which had fallen to Islamic expansion as early as the 7th century. The People’s Crusade failed but was immediately followed by the successful Princes Crusade, which was a well organised military campaign. This was followed by 2 failing crusades before the well known 3rd Crusade of Richard I which ended with a 3 year truce – The Treaty of Jaffa. Many more crusades happened in succeeding years with various levels of success and failure.

Peasants in the 12th and 13th century.

The word ‘Peasant’ means ‘Country Man’. Ten percent of the population were slaves in the Middle Ages; people who were bought and sold and could not own property. A further 75% were cottars, bordars or villeins, who worked the land for their Lord. It isn’t true that peasants were uncouth. Excavation of a medieval village in Yorkshire showed that they had a neat, planned village and lived in families much as we do now. The villeins organised care of their Manor through the Manor Court, planning how fields were to be farmed, dates for planting and harvesting, and the boundaries of the strips of land held by each villein. The courts also determined the dates on which the animals were allowed to graze in different fields. They worked together to the benefit of the village as a whole.

Medicine

In the 12th century medicine was made up of 3 different parts: Doctors, Pilgrimage and Witchcraft. In the 12th century the most famous medical school was in Southern Italy, where both male and female could study. It was reputedly founded by a Christian, an Arab and a Jew. People also took pilgrimage to a Holy shrine and many sick people received miraculous cures. As the Doctor cost too much for most people, they turned to witches who had potions and ointments passed down from their mothers.

Sherwood Forest

We also looked at the impact of Sherwood Forest on the East Midlands. William the Conqueror created the Norman forest system in England which claimed exclusive hunting rights for the King. No-one but the King was allowed to kill deer, wild boar, hares, rabbits, wildfowl and birds used in falconry, or to fish in ‘forbidden rivers’ or to chop down trees and other forms of vegetation which afforded food and shelter for game. Henry II enforced the laws firmly and enlarged the forests. Forest inhabitants were not allowed to have bows and arrows or any other tool that would allow them to kill game. Their rights to cut wood for building and fuel and to pasture their animals on the wasteland was restricted. Many people became ‘outlaws’ under this strict regime.

October 2018

RICHARD I

In October we looked in detail at Richard I. He was also known as Richard the Lionheart, a title he gained in the 3rd Crusade to recapture the Holy Land from the Muslims. He came to the throne at the age of 34. Richard’s opinion of England was that it’s always cold and raining. He reigned for 10 years but spent no more than 6 months here. His wife Berengaria never set foot in England.

He was Eleanor (his mother) of Acquitaine’s favourite child and she wanted him to rule her kingdom in France. He fought alongside his brother, against his father, for her French lands but lost the battle. His father forgave his sons but he didn’t forgive his wife for conspiring against him and Eleanor was imprisoned until Henry II died.

Richard left the Holy Land in 1192 and in January 1193 he was captured and delivered to Emperor Henry VI. The dowager Queen Eleanor, at the age of 70, arranged his freedom. In 1199 at the siege of Chalus he was wounded and died several days later when the wound turned septic.

We also looked at several Medieval English phrases which we still use today e.g. Throw down the gauntlet – a knight would cast one gauntlet to the floor to challenge a fellow knight or enemy; Hue and cry – the French word ‘huer’ meant to shout out. In the middle ages you were obliged to shout and make a noise to warn the community to give chase if you saw a crime being committed; etc.

September 2018

THE PLANTAGENETS(2)

This month the group continued to investigate the Plantagenets and also looked at the food that was eaten in the Middle Ages.

Food

Many of the eating habits were dictated by the rule of the Catholic Church with many fast days. Food was seasonal and eating it was dependent on complex systems of trade. The rich ate lots of fish and meat, enhanced with exotic spices and honey. They imported and used a large number of almonds and drank almond milk in preference to cow’s milk

Poor people had a much less varied diet: mainly pottage made from peas and beans. They also ate rye or barley bread, perhaps a bit of bacon. Grain provided 65-70% of calories in the early 14th century. So, their health was very dependent on the success of the harvest. Along with their grains, peasants ate cabbage, beets, onions, garlic and carrots. Cheese was the most common source of animal protein for the lower classes and many of the varieties would look familiar today, like Edam, Brie and Parmesan.

Medieval Europeans typically ate two meals a day: dinner at mid-day and a lighter supper in the evening. During feasts, women often dined separately from men due to social codes; or they sat at the table and ate very little. Plates were non-existent. Instead, people used the bottom part of a loaf of bread; or in lower-class households, they ate straight off the table.

Law

Henry II is sometimes known as the “Father of the Common Law”. He reformed the law and set up the jury system. He ordered that only royal judges (Justices) could try criminal cases and cases involving disputed ownership of freehold property. The Justices were sent to tour the Counties on a regular basis (Circuits). Throughout the medieval period it was believed that the only way to keep order was to ensure that people were scared of punishments handed out for crimes; from stealing to murder, they were all harsh. Although there were gaols, these were generally only used to hold prisoners awaiting trial.

Battles

Henry was an opportunist, exploiting chances he was given to consolidate power. He never went to war personally, but persuaded others by offering inducements to rule territory, while keeping them beholden to him, therefore creating a vassalage system in which the personality of the King is central. He saw himself as Lord of his domain, which included England, Normandy, Maine, Anjou and on the periphery, Brittany and Wales.

Henry mounted 3 punitive campaigns into Wales between 1157 and 1163 which reasserted Royal authority; however he over-reached himself in 1163 attempting to define his rights as feudal overlord of the Welsh Princes by demanding oaths of vassalage of them. The Welsh rebelled and Henry responded in 1165 with the largest military campaign in Wales but he was defeated by the difficult terrain and bad weather. The Welsh meanwhile continued to encroach on the land of the Norman Barons and was the reason that the Normans moved into Ireland. Initially unconcerned, Henry eventually closed all the ports to Ireland, ordering all those who had crossed to return and threatening to confiscate their lands if they didn’t return. In the meantime, the men of Wexford had risen up against Robert the Normans. The Irish appealed to Henry for aid and the men of Wexford offered Robert FitzStephen as the man who had initiated the Norman encroachment into Ireland. Robert languished in prison until 1172.

Henry landed in Ireland in 1171 and was met by the sub-kings of Leinster and other kingdoms, who did homage to him. Henry left Ireland in 1172 leaving Strongbow in charge of Leinster, but with the importantly strategic locations of Wexford, Leinster, Cork and Wicklow castle in royal hands. Like Wales, once the situation of Ireland had been resolved Henry seemed to have lost interest. He seemed much less concerned with conquering territory than with exerting, what might be termed, as feudal control over his neighbours.

July 2018

THE PLANTAGENETS(1)

At the July meeting the group began to look at the Plantagenets. We learnt that the name Plantagenet came from Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, who wore a yellow broom flower (planta genista) in his helmet. He married Empress Matilda, the daughter of Henry I and their eldest son became Henry II.

The Plantagenets were the longest reigning English dynasty and many elements of what we today know as England were founded in this time. Borders of the realm were established; principles of Law and Institutions of Government that have endured to this day were created; A rich mythology of national history and legend was concocted and cults of two of our national saints, Edward the Confessor and St George were established.

Military tactics were revolutionised from the Norman age of siege craft to pitch battles with the English men at arms and the deadly mounted archers – the scourge of Europe. England also began to explore war on the open seas. In the middle of the 14th century something resembling an English Navy could be deployed to protect the coasts and attack enemy shipping.

By the end of the Plantagenet reign England had been transformed into one of the most sophisticated and important kingdoms in Christendom. This period ended with the War of the Roses and took us out of the Dark Ages into the nation we recognise today.

We also looked at significant buildings from the period:

St Julienne Cathedral in Le Mans, France where Geoffrey Plantagenet and Empress Matilda were married and Geoffrey was buried. Henry II was also baptised there and he funded refurbishment which included buttresses: a new development in this period.

Canterbury Cathedral where Henry II’s knights hacked Thomas Becket to death and Henry was ritually flogged by all the monks of the cathedral as penance.

Kenilworth and Caerphilly Castles, where water defences were created and the design included concentric rings of walls which proved to be a turning point in the history of the castle in Britain. Both of these castles were significant in the overthrow of Edward II in 1326/7

Henry II and Eleanor (Alienor), Duchess of Aquitaine

We learnt that Henry II was full of energy and drive; he was keen to assert his authority and restore the lands and privileges held by his grandfather Henry I. By the end of 1155 he had restored a semblance of order and sound administration to much of England. As Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou he had control over Normandy, Anjou, Maine and Touraine; and by marrying Eleanor he extended his land to include Aquitaine. His French lands stretched from the English Channel to the Pyrenees and covered ten times as much of the country as the French Kings’ possessed. By 1172 he controlled England, large parts of Wales, the eastern half of Ireland and the western half of France, an area that would later come to be called the Angevin Empire.

Henry and Eleanor had 8 children and their descendents ruled for 2 centuries. Two of their sons Richard II (Lionheart) and John followed Henry as rulers of the Angevin Empire.

May/June 2018

THE NORMANS

The Norman Kings

This period of history began with William I – William the Conqueror – in 1066. After the Battle of Hastings on 14th October, he was crowned at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. He is credited with the introduction of Feudalism Law and a survey of England know to us as The Domesday Book.

Next in line was William’s 3rd son William II – Rufus or The Red King. He reigned from 1087 to 1100. He proved to be most unpopular, especially with the church because of his opposition to reform. He also used church revenues for his own use and his promiscuous homosexual lifestyle. He had no children.

Henry I – reigned 1100 to 1135. William II’s younger brother Henry I secured the throne while his older brother Robert was absent on a crusade. He was crowned King at the age of 32 and he reigned for 35 years. He had 21 illegitimate children. He was a good diplomat and was known as the Lion of Justice. He declared his daughter Matilda his Heiress.

Stephen – reigned 1135 to 1154. On the death of Henry I, Stephen claimed the throne, despite the fact he had sworn to help Matilda succeed her father. Historians generally agree that Stephen was the worst King of England. Most of his reign was at war. In 1148 Matilda left the country for France and in 1153 her son Henry was old enough to take up the fight for the throne. Henry agreed with Stephen at the Treaty of Winchester that he would leave Stephen to rule if Stephen named him as his heir. On Stephen’s death Henry became King Henry II and started the House of Plantagenet.

The Norman Battles

In January 1066 Edward the Confessor died childless. He had promised the throne to both Harold Goodwinson and Harald Hardrada (King of Norway), although several other people wanted to be king, including William of Normandy. On Edward’s death Harold Goodwinson was immediately crowned King Harold II.

Harald Hardrada invaded Yorkshire with approx. 300 longships, and defeated the northern Saxon army at the Battle of Fulford. Harold II marched North, gathering more army recruits on his way. He took Hardrada by surprise and defeated him at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on the 25th September 1066.

While Harold II was in the North of England, William, Duke of Normandy, invaded Sussex with a fleet of 700 ships and a large army. King Harold rushed back to the South. On the 14th October 1066 the 2 sides met at Senlac Hill, Near Hastings. William had a well-equipped army, with Knights on horseback and archers with crossbows, whilst Harold II’s army were on foot with only axes and the Fryd (working men – mainly farmers – called up by kings to form an army) had anything that they could use to fight. William used his archers to break up the shield wall and Harold’s soldiers then surrounded him for protection, but he was killed, possibly with an arrow in his eye.

William was crowned King of England on Christmas Day 1066, but it took years more fighting to conquer the Country. Some English people rebelled against the new leader, including Hereward the Wake in East Anglia and Eadric the Wild in Shropshire. The biggest rebellion was in Northern England in 1069. In the North East of England, he ordered villages to be destroyed and people to be killed, together with herds of animals and crops being burnt. Most of the people who survived starved to death, even, allegedly turning to cannibalism. This is called “The Harrying of the North”.

The Norman Conquest broke all links with Denmark and Norway and connected the country to Normandy and Europe. William got rid of all Saxon nobles and imposed the feudal system on England. William reorganised the Church in England and brought in men from France to be Bishops and Abbots. Great Cathedrals and huge monasteries were built. Tensions between the English and their new French rulers lasted for over three centuries.

Norman Castles

Before the Normans arrived there had not been much construction for defensive purposes. The castles they built initially were motte and bailey – an internal stronghold with a larger enclosure surrounding it. Within this enclosure were various wooden buildings such as stables, kitchens etc. These castles could be constructed quickly with materials that were ready to hand and were easily defended by a small number of troops. Over 500 motte and bailey castles were built in William I’s reign, although many were built by the barons he appointed in order to secure their own land. The earthwork form of several mottes has survived to the present time.

William built his castles as he moved up country and he thought nothing of destroying existing buildings along the way. He wanted to show Norman superiority. He faced a lot of uprising, especially in the North.

By the middle of the 12th century many castles had been rebuilt in stone or had stone structures added. The White Tower of London is the best example of a Norman keep. The height of the keep and the massive walls (e.g. Dover Castle walls 20ft thick) meant that the enemy were unable to demolish them and gain entry to the castle. However they were vulnerable to attack on the corner of the rectangular keeps and by the late 12th/early 13th century circular and polygonal keeps were emerging.